History of Cremation - Kopieren - www.crematorium.eu informs about crematoria in Europe- Krematorium.eu- crematorio.eu, find a crematorium

History of Cremation - Kopieren

Ancient

Cremation dates to at least 20,000 years ago in the archaeological record with the Mungo Lady, the remains of a partly cremated body found at Mungo Lake, Australia.

Alternative death rituals emphasizing one method of disposal of a body—inhumation (burial), cremation, and exposure—have gone through periods of preference throughout history.

In the Middle East and Europe, both burial and cremation are evident in the archaeological record in the Neolithic. Cultural groups had their own preference and prohibitions. The ancient Egyptians developed an intricate transmigration of soul theology, which prohibited cremation, and this was adopted widely among other Semitic peoples. The Babylonians, according to Herodotus, embalmed their dead. Early Persians practiced cremation, but this became prohibited during the Zoroastrian Period. Phoenicians practiced both cremation and burial. From the Cycladic civilization in 3000 BC until the Sub-Mycenaean era in 1200–1100 B.C., Greeks practiced inhumation. Cremation appearing around the 12th century B.C. constitutes a new practice of burial and is probably an influence from Minor Asia. Until the Christian era, when the inhumation becomes again the only burial practice, both combustion and inhumation had been practiced depending on the era, and area. Romans practiced both, with cremation generally associated with military honours.

In Europe, there are traces of cremation dating to the Early Bronze Age (ca. 2000 B.C.) in the Pannonian Plain and along the middle Danube. The custom becomes dominant throughout Bronze Age Europe with the urn field culture (from ca. 1300 B.C.). In the Iron Age, inhumation becomes again more common, but cremation persisted in the Villanovan culture and elsewhere. Homer's account of Patroculus burial describes cremation with subsequent burial in a tumulus similar to Urnfield burials, qualifying as the earliest description of cremation rites.

This is mostly an anachronism, as during Mycenaean times burial was generally preferred, and Homer may have been reflecting more common use of cremation in the period in which the Iliad was written centuries later.

Criticism of burial rites is a common aspersion in competing religions and cultures, and one is the association of cremation with fire sacrifice or human sacrifice.

Hinduism and Jainism are notable for not only allowing but prescribing cremation. Cremation in India is first attested in the Cemetery H culture (from ca. 1900 B.C.), considered the formative stage of Vedic civilization. The Rig-Veda contains a reference to the emerging practice, in RV 10.15.14, where the forefathers "both cremated (agnidagdhá-) and uncremated (ánagnidagdha-)" are invoked.

Cremation remained common, but not universal, in both Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. According to Cicero, in Rome, inhumation was considered the more archaic rite, while the most honoured citizens were most typically cremated—especially upper classes and members of imperial families.

Christianity frowned upon cremation, both influenced by the tenets of Judaism, and in an attempt to abolish Graeco-Roman pagan rituals. By the 5th century, the practice of cremation had practically disappeared from Europe.

In early Roman Britain, cremation was usual but diminished by the fourth century. It then reappeared in the fifth and sixth centuries during the migration era, when sacrificed animals were sometimes included with the human bodies on the pyre, and the deceased were dressed in costume and with ornaments for the burning. That custom was also very widespread among the Germanic peoples of the northern continental lands from which the Anglo-Saxon migrants are supposed to have been derived, during the same period. These ashes were usually thereafter deposited in a vessel of clay or bronze in an "urn cemetery." The custom again died out with the Christian conversion among the Anglo-Saxons or Early English during the seventh century, when inhumation of the corpse became general.

In the Middle Ages

Throughout parts of Europe, cremation was forbidden by law, and even punishable by death if combined with Heathen rites. Cremation was sometimes used by authorities as part of punishment for heretics, and this did not only include burning at the stake. For example, the body of John Wycliff was exhumed years after his death and cremated, with the ashes thrown in a river, explicitly as a posthumous punishment for his denial of the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation. On the other hand, mass cremations were often performed out of necessity, when there was a fear of contagious diseases, such as after a battle, pestilence, or famine. Retributory cremation continued into modern times. For example, after World War II, the bodies of the 12 men convicted of crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg Trials were not returned to their families, but were instead cremated, then disposed of at a secret location as a specific part of a legal process intended to deny their use as a location for any sort of memorial. In Japan, however, erection of a memorial building for many executed war criminals, who were also cremated, was allowed for their remains.]

The modern era

In 1873, Paduan Professor Brunetti presented a cremation chamber at the Vienna Exposition. In Britain, the movement found the support of Queen Victoria's surgeon, Sir Henry Thompson, who together with colleagues founded the Cremation Society of England in 1874. The first crematoria in Europe were built in 1878 in Woking, England and Gotha, Germany. The first cremation in Britain took place on 26 March 1886 at Woking.

Cremation was declared as legal in England and Wales when Dr. William Price was prosecuted for cremating his son; formal legislation followed later with the passing of the Cremation Act of 1902 (this Act did not extend to Ireland), which imposed procedural requirements before a cremation could occur and restricted the practice to authorised places.

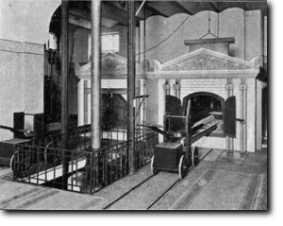

Crematorium Stuttgart 1906

Ruppmann cremation system

Some of the various Protestant churches came to accept cremation, with the rationale being, "God can resurrect a bowl of ashes just as conveniently as he can resurrect a bowl of dust." The 1908 Catholic Encyclopedia was critical about these efforts, referring to them as a "sinister movement" and associating them with Freemasonry, although it said that "there is nothing directly opposed to any dogma of the Church in the practice of cremation." In 1963, Pope Paul VI lifted the ban on cremation, and in 1966 allowed Catholic priests to officiate at cremation ceremonies.